Does the right to freedom of speech include the right to be wrong?

There is a touch of irony in one of the defining characteristics of the Information Age being #FakeNews, and in recent years the impacts and origins of #FakeNews have become the subject of much research. A Council of Europe report describes the term as “woefully inadequate to describe the complex phenomena of information pollution”, and that because it has been “appropriated by politicians around the world to describe news organisations whose coverage they find disagreeable” it is “becoming a mechanism by which the powerful can clamp down upon, restrict, undermine and circumvent the free press”. The report opts instead to use the term Information Disorder, and uses harm and falseness to divide the types of information into three sub-categories:

- Mis-information: When false information is shared, but no harm is meant

- Dis-information: When false information is shared with the intention to cause harm

- Mal-information: When genuine information is shared with the intention to cause harm, typically by publicly sharing information meant to stay private

Tackling information disorders is a complex and multifaceted problem for various institutions within the scientific establishment. These include fringe movements such as “9/11 truthers” rejecting the analyses from engineers, material scientists, and demolition experts over the collapse of the World Trade Centre towers (#JetFuelCantMeltSteelBeams), to more well-known anti-science movements such as the Flat Earthers, anti-vaxxers, and the anti-GMO movement. For the large part I don’t think we as a society take these movements, and information disorders as a whole, as seriously as we should. However, as the COVID-19 pandemic grips the world, the narrative around information disorders has shifted. Multiple countries, including South Africa, have criminalised the spreading of false information surrounding the disease and this has raised the question of whether our right to freedom of speech includes the right to be factually incorrect.

As scientists we can get lulled into thinking those who perpetuate information disorders are an isolated group with whom we have little contact, but this is not the case. Recently a family member of mine posted a lengthy status on Facebook relating to the COVID-19 pandemic. The post claimed that the virus was a plot to destabilise the capitalist economies of the Global North, that communist countries had not been affected by the virus, and that the Chinese government already had a cure that was being hidden from the world but used to treat their own citizens. This post was one of the many I had seen discussed online, dripping with racist, sinophobic, and anti-science rhetoric. The only difference was not an abstract example on someone else’s timeline, but a very real post by a healthcare professional I knew personally. I wholeheartedly believe that we all have an obligation to tackle information disorders wherever possible, particularly when it is perpetuated by those close to us.

In our exchange, the poster (Person X) justified their sinophobia by referring to the reported brutalities of the Chinese government and the cultural differences in animal consumption between Western and Eastern societies. However, this is both an example of othering and whataboutism that only seeks to divert the attention from the racism and sinophobia under question. As Jonathan Kolby states in Coronavirus, pangolins and racism: Why conservationism and prejudice shouldn’t mix “environmentalism and conservationism are noble and vital pursuits” but “dialogues about coronavirus should not allow the topic of wildlife conservation to provide a smokescreen for prejudice”. Gerald Roche gives a superb discussion on the wider societal effects of this in The Epidemiology of Sinophobia, but this is not what I want to focus on for this post.

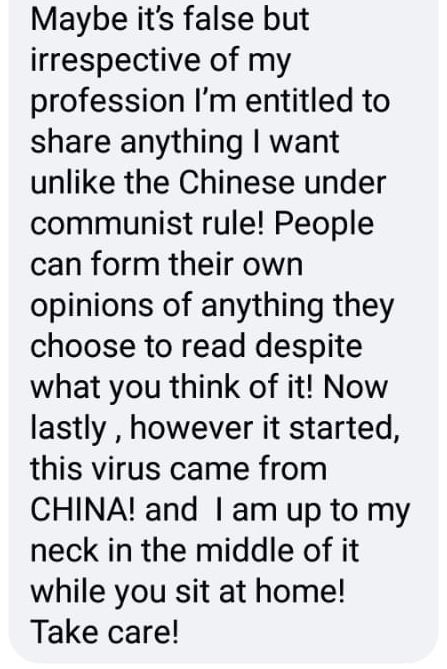

On top of trying to justify their prejudice, Person X posted follow-up comments with information that was more scientifically sound but in direct contradiction to the original post. Person X justified this by saying that they were not an expert in this field, that the original post was copied and pasted from an unknown source, and that their intention was to present information from both sides. The interaction between myself and Person X ended with the following comment, after I questioned why in the midst of a pandemic a medical professional would choose to share false information that could easily have been verified before posting:

Person Y came to the defence of Person X stating that we are all entitled to our own opinions regarding the virus, and that they are “not really phased what that is” but “when [I] sit behind [my] phone or laptop and comment away while people are putting their lives at risks and in the trenches fighting all over the world, just be careful what [I] say. If [I] know everything about the “claims” then [they] would recommend going to assist with fighting this virus, fruit salts.”

The sentiments of both these people raise three questions:

- Does sharing information from multiple sources in an effort to present all sides of a story make one guilty of contributing to an information disorder if the information is factually incorrect?

- Is everyone entitled to an opinion, no matter how falsified it is?

- By virtue of their work, are frontline workers above criticism for their opinions?

To answer these questions we need to look with both a scientific and legal mind, which is a unique opportunity the COVID-19 pandemic provides us. At the time of writing this, at least eight people had been arrested for being in violation of COVID-19 Disaster Management Regulation 11(5). This regulation states that “any person who publishes any statement through any medium, including social media, with the intention to deceive any other person about a) COVID-19, b) COVID-19 infection status of any person, or c) any measure taken by the Government to address COVID-19 commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a fine or imprisonment for a period not exceeding six months, or both such fine and imprisonment”. What is important here is how intent is defined. In this instance the legal definition of intent is not just a person meaning to deceive others by sharing false information (Dolus directus), but also a person seeing the possibility of others being deceived before sharing the false information (Dolus eventualis) or a person genuinely believing the shared false information to be true themselves (Dolus indirectus). The three legal definitions of intent align quite heavily with the three categories of information disorders.

This legislation places a responsibility on all of us to check the validity of the information we are spreading, and I hope going forward this experience places this responsibility in the forefront of our collective conscience. If we do not know enough or are not willing to critically evaluate information that is presented to us, a safer option would be to not perpetuate the information at all. In The Salmon of Doubt Douglas Adams penned, “All opinions are not equal. Some are a very great deal more robust, sophisticated and well supported in logic and argument than others”. A central tenant of a democracy is the right to hold an opinion, but these opinions should not shielded from criticism and debate. In fact, one of the health indicators of a democracy is the quality of the debates. In doing this however, we must critically assess which opinions are worth debating, discarding those not founded upon evidence instead of debating for the sake of debate.

I believe the desire to share all sides of a story is a result of how the media has approached presenting complex stories in the past. All too often we see panels consisting of experts such as medical virologists and meteorologists seated alongside non-experts such as anti-vaxxers and climate-change denialists, for the sake of “balance”. This gives a false legitimacy to the side whose opinion is not supported by scientific evidence. I advocate for deplatforming people who hold opinions and beliefs that go against established scientific theory, such as the safety of vaccines, the effectiveness of genetic modification as a breeding tool, or the impacts of anthropogenic climate change. This is not to say that I don’t believe that these complex topics have nuance which needs to be unpacked debated, but rather that we would make better use of our time debating amongst experts over said nuance rather than with those who reject reality. This includes “front-line” workers of all types.

I believe the responsibility of ensuring your opinion is backed by facts is heightened when you are in a position of perceived authority as a front-line worker. In this instance I regard anyone who works directly with the public as a “front-line” worker, as these professions will have the largest influence on public opinion. In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, when front-line workers such as nurses and doctors share false information, they undermine the work and credibility of the entire industry that supports them. The is includes everyone from the virologists working on understanding the virus, to the research groups working on developing a vaccine, to medical researchers working on developing treatment protocols, to government agencies trying to coordinate disaster relief efforts and reduce the spread. In perpetuating false information, these front-line workers reduce public support for these highly coordinated efforts, eroding the public’s trust in the scientific establishment, increasing tensions both locally and globally, and ultimately costing us lives as the public becomes less likely to follow guidelines aimed at reducing the spread of the virus.

Too many lives have already been lost from information disorders surrounding life-saving technologies such as vaccines and biofortified GM crops. If there is only a single positive thing to come out of the COVID pandemic, I truly hope that it is us a society taking the threat of information disorders more seriously.

Richard Hay