It’s been 29 years since South Africa’s first democratic elections (27 April 1994), and there is a lot to reflect on since then. Understanding what it means to embody freedom has many different connotations as well. A famous Nelson Mandela quote about freedom says the following:

“For to be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.”

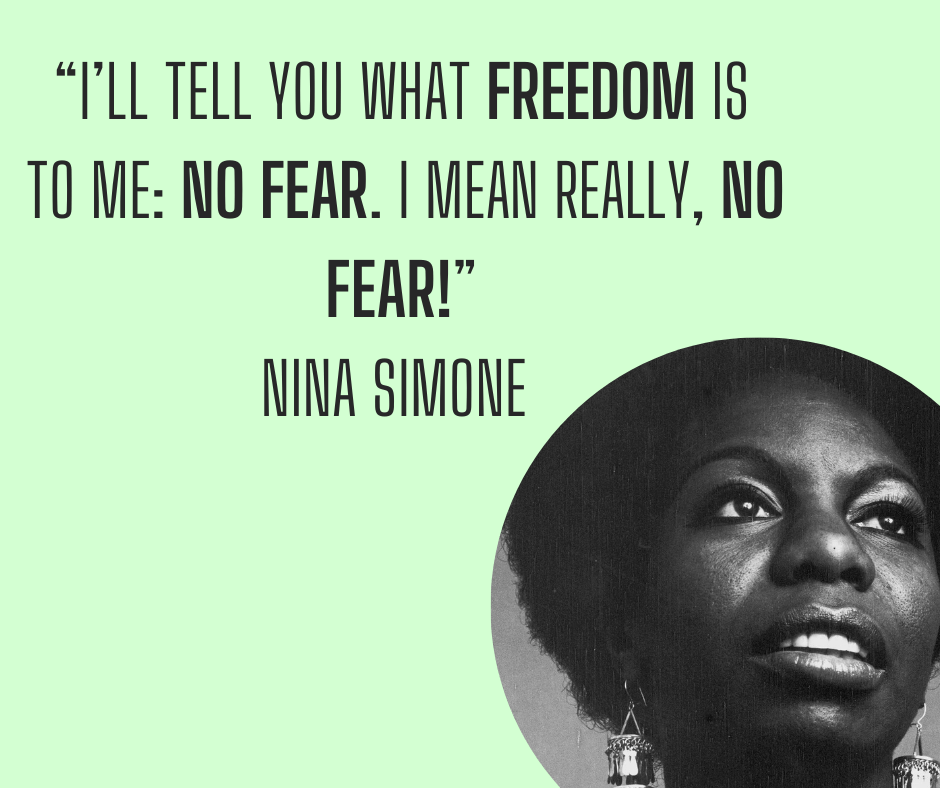

Additionally, famous activist and singer Nina Simone said the following about freedom:

With this in mind, it is crucial to reflect on how we can ensure freedom is not only about celebrating the strides made since 1994 but also what it means to see freedom as a practice. I will take us through three examples of some prevalent socio-economic inequalities that still exist in South Africa (and the continent) today that require us to remain advocates for a just society.

Equality as a form of Freedom

The first one is gender equality. According to the National Strategic Plan on Gender-based Violence and Femicide, South Africa’s high rates of structural Gender Based Violence (GBV) is tied directly to an unequal country. What this means is that for vulnerable members of our population (women, children, LGBTQIA+ persons), the promise of freedom can only go far as it is written on paper. We need to be aware of how gender inequality affects all of us because how we treat marginalised bodies has ramifications on our own freedoms in the future.

The Freedom to Live in South Africa

As mentioned in my first blog post, my Master’s thesis explored the experiences of West African migrants living in South Africa. Although the study looked at a focus group, iterations of xenophobia against African migrants exist on a larger scale. Anti-immigrant sentiments in groups like Operation Dudula set a dangerous precedent for how we create ‘us vs. them’ mentalities, negating the Pan-African values necessary for socio-economic development and prosperity for all.

Freedom to obtain a good quality of life

This ties into the third inequity, which is the right to have a quality of life that enshrines human dignity. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) states that since 1990, 10% of the global population lives in extreme poverty (down from 36% in 1990). Yet if we are to contextualise this statistic in Africa, the wide gap in systemic inequality between Africa and the rest of the world highlights how much work can still be done. Eradicating poverty in Africa is crucial for promoting our freedom, as poverty can limit individuals’ ability to access education, healthcare, and economic opportunities. According to the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), Africa has the largest share of extreme poverty rates globally, with 23 of the world’s poorest 28 countries at extreme poverty rates above 30% By addressing poverty, we can improve the overall well-being of individuals and communities, empowering them to lead more fulfilling lives and participate in shaping their own future.

Final thoughts on freedom

By understanding freedom as a fundamental right that we all have, it is imperative that we know our power as a collective of human beings who want our planet to survive and thrive. As mentioned in the first quote by Mandela, the only way to ensure freedom as a practice is through practising compassionate concern for your fellow human being. Although the future remains somewhat unknown, now more than ever, it is important for us to be aware of our realities, and how they relate to others, and to trust that we are vigilantly building towards the kind of future we envision with kindness and hope. In the words of Nina Simone, without fear. We cannot contemplate without being aware that the impetus for change has evolved into something more foreboding than a ticking clock. As such, regardless of the work that we do, there is always a way to strive towards the betterment of humanity.