The science of sleep weaves together nearly every other discipline of medicine. In fact, the curiosity around why we sleep and what sleep can and cannot accomplish for us binds the book of the human experience. I’d be so bold as to say that for as long as Homo sapiens have been communicating, part of that ancient communication has centred around dream recall, symbol interpretation, and ancestral connection.

There was clearly a lot of speculation that came with the phenomena of sleep states, some of which has shifted over the last 200 000 years or so into unanimously accepted “truths”. As sleep is a procedural change from one state of awareness into another, I thought I’d tell a “bedtime” story of that process rather than alphabetically list these terms…

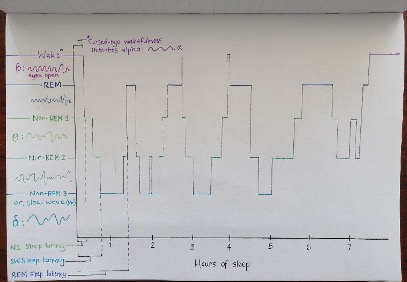

You’ve assumed your comfy spot at the end of a long day. Your eyes delicately blink closed, shutting out the visual stimulation of wakefulness. Your state of consciousness – no, not some esoteric interpretation of enlightenment – speaks to the relative arousal or alertness of your brain activity, characterised by electrical activity between several regions of the brain. From wakeful awareness, your conscious state will slow down into “alpha, delta and theta” states that indicate the initiation of various sleep stages. This slowing is called sleep latency: the time it takes to reach a certain stage of sleep. The initiation of sleep is not only a function of tiredness and closed eyes. At various times over a given 24-hour cycle, our internal body clock releases certain neuromodulators. These are chemical messengers which brain cells communicate through, sending the global signal of “okay, time to slow down these brainwaves and get to bed!”

Though everybody has a different pattern of sleep stages, a standard hypnogram – which is the graph representing sleep stages – follows a particular pattern. Usually, the early parts of your sleep are focused on slow wave sleep, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep increases through the night. REM is when your limbs are inactivated from bodily arousals, and your eyes move quickly, as the activity in your brain resembles a hustle and bustle that is representative of wakeful awareness, or beta brainwaves.

How do we measure the shifts in conscious awareness? Electrodes are placed on areas of the scalp, with an allocated reference point depending on which map of the brain the sleep scientist is following. Commonly, we use a 10-20 system for electrode placement; the distance between electrodes follows a universal spacing ratio despite people having heads of all shapes and sizes! The electrodes must have a low signal impedance, meaning that the interference of the environmental electrical energy (and, strands of hair or dead skin cells) does not confound the beta, alpha, delta, and theta brainwave formations which we are able to read.

From the sleep recording, called a polysomnogram, we are also able to measure the change of a person’s nocturnal oxygen saturation. Your red blood cells are responsible for oxygenating the blood; reduced “sats” suggest that the oxygen supply to the body from the oxygen available in the blood is being disrupted.

Some truly fascinating things occur in your body while you are asleep. For one, your brain has its very own detoxification system, known as the glymphatic system. Disposal of waste products – like small protein segments or unused chemical byproducts – by the glymphatic system during sleep helps to maintain a healthy nervous system. This prevents the build-up of molecules that cause neurological harm. Another important reason for getting good sleep is memory consolidation. Research supports that as your brain solidifies the things you learned or experienced during the day, a memory is replayed with a few creative additions and fictional musings; potentially, this is how memories are theorized to played out as our dreams.

Before you know it (because you’re in dreamland, of course), the internal body clock kicks in again, releasing the neuromodulators which encourage you to wake up from sleep. Your brainwaves speed up, and the connectivity between many areas of your brain is increased. In good health, you are likely more alert; rested; detoxified; and prepared to have an energized day.