– Professor Alfred K. Njamnshi, founder of Brain Research Africa Initiative

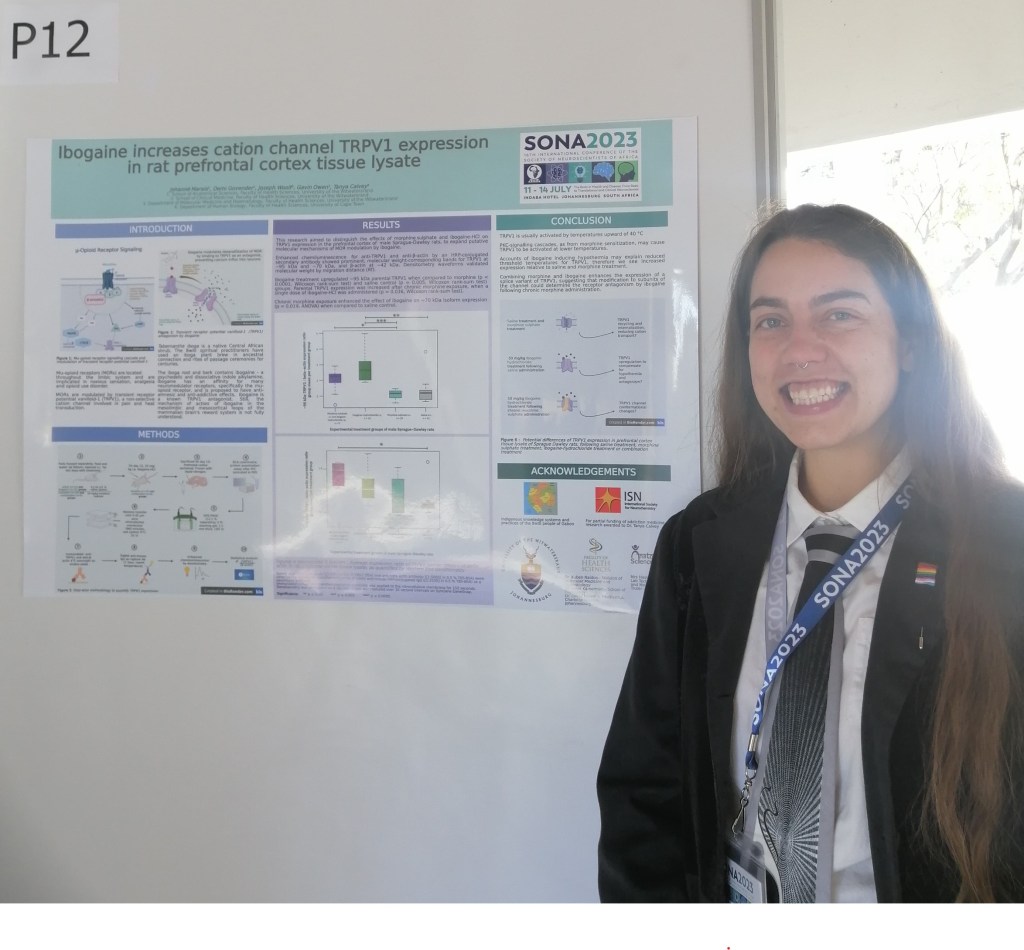

During a daily email scan on some day in May, I read that my research project had been accepted for a poster presentation at a conference I had applied to. Imagine that! For specialists, early career researchers, graduate students, and established professors alike, conferences offer an opportunity to touch base with current prospects (and persons) of a particular field.

Many anticipatory weeks and several hours of design later, I made my way to the venue – printed poster proudly in hand. Being socially anxious yet outspoken and opinionated (read: awkward), I felt a little uneasy about how the week would play out. Most of this was settled when I met a Twitter™ friend, Arish. We sat in the sun, exchanging warm parcels of chit-chat some hours before the first plenary speaker, Prof. Njamnshi, officially opened the conference.

My recounting of the conference is cherished in journal pages and short-hand notes. I could probably write a Master’s thesis on my experience. Though, in the absence of 150 pages available for my storytelling, I will offer you the abstract:

Introduction: Some 30-odd years ago, in Kenya’s city of Nairobi, the Society of Neuroscientists of Africa was registered. What began as a handful of African neuroscientists coming together to amplify African neuroscientific research has now grown so vastly that nearly 300 keen delegates are affiliated members of the society. Some of these delegates from 19 African countries – and 34 countries worldwide – congregated at the 16th Biennial International Conference of the Society of Neuroscientists of Africa (SONA), held in Johannesburg in the middle of July.

Aims: According to the society’s webpage, SONA aims “to promote research, teaching and advocacy in neuroscience in Africa…”. I arrived at the conference with my own aims, though. I intended to remain humble but secure in my knowledge basis, while being receptive to learning new topics unfamiliar to me. I sought to meet and engage with as many neuroscience enthusiasts from the continent as what my social capacity would permit, to begin forming my own “neural network” for collaborations and research support.

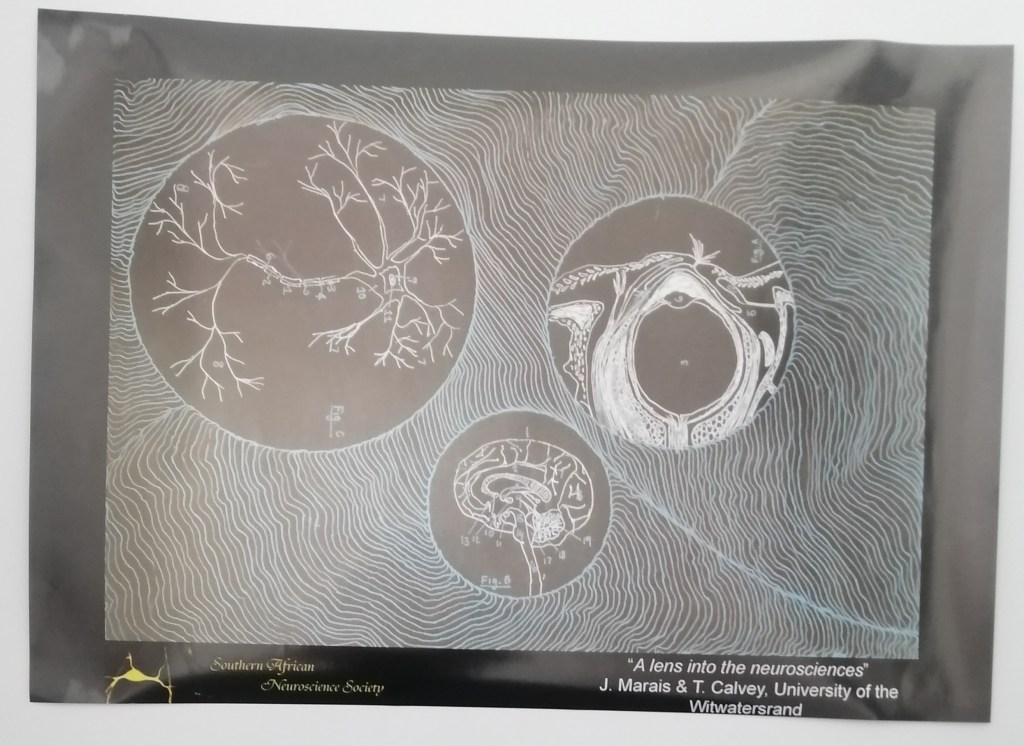

Methodologies: An array of symposia, workshops, poster presentations and communal meals gave attendees the opportunity to ask questions, share their work, rub shoulders with giants and shake hands with mentors and friends. The theme, “The Brain in Health and Disease: From Basic to Translational and Clinical Neurosciences”, stimulated provocative and challenging conversations across the multidisciplinary niches. Notebooks embellished with SONA aesthetics sat back-to-back with a printed program in each person’s complimentary tote bag, so that they could plan their preferences over the four days.

Results: From cell culture to measuring protein expression; patient-facing clinical research to data sharing… Neurosciences are diverse and expansive! The underlying message which unified all the sessions was the importance of shifting focus to research that was locally relevant but internationally applicable. Formal neuroscientific teaching now spans 70 % of the 54 African countries, and there was a conference-wide encouragement for teaching centres to continue boasting investigations by Africans, for Africans.

A broad contribution was made by researchers studying neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s; similarly, by those who work at the intersection of neurosciences and the immune system. Some important buzz terms that permeated the air were “neurodiplomacy”, “FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable) brain data” and “neuroethics”.

Conclusion: As a postgraduate researcher, I have days where I feel in limbo: neither entirely a student nor a staff member. At the SONA conference, this felt different. Most people were less phased by using titles or the accolades that follow their name than they were about actively engaging with other attendees. By the final day, I was so diversely besotted with the neurosciences (and the neuroscientists) of the continent that the thought of following just one path to the future was entirely unsatisfying.

In the absence of clarity for the “what” question of research, I found myself re-establishing my answers to how; why and where. As Prof. Njamnshi implored, good science comes not from publishing papers but rather from having strong vision, acting on accomplishable goals, living with passion and creating a purpose. The aims of SONA – and my own – had been surpassed.