In October 1927, the Solvay conference (a prestigious invite-only Physics meeting) was in session. In one room were Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Max Planck and even Erwin Schrödinger. 17 of the 29 attendees would go on to win Nobel prizes, with Marie Curie achieving that honour in two fields. Pictured below is the historic photo (recently colourised by Sanna Dullaway) to serve as proof that those coffee breaks must have been the greatest in history.

These individuals would decide the course of quantum physics at this meeting, what was to come and what the field is now was down to them.

Why do we oooh and ahhh at the guest list of the Solvay conference? People have an obsession with genius. And as scientists, perhaps we have a wish to emulate them. One of the ways to do this is to look at those individuals that have managed to completely distinguish themselves from all other scientists by winning the Nobel Prize.

So what are the trends? Well for a start, it is best not to be a woman. Of the 900 Nobel laureates, only 49 are of the fairer sex. Furthermore, it’s best to be an American, as a whopping 257 individuals have been born there (29%, as compared to 1% of the winners being South African). It is also best if you have a birthday on 21 May or 28 February and happen to be 61 years old at the time of the award. Oh, and be a Harvard affiliate (26 were). The Curie family had 6 Nobel Prizes in the extended family (Marie received 2, Pierre her husband, shared one with her in 1903; their daughter Irène Joliot-Curie and her husband Frederic shared one in 1935 and in 1965 Marie’s second daughter’s husband received the Nobel Peace Prize. There have been 5 married couples, 1 sibling and 8 parent-child pairs of laureates – so perhaps working with family is the best thing to do. Basically, your best chance of winning a Nobel Prize, statistically, is to be a 61 year old male physicist who works for Harvard or Caltech (who have so many Nobel laureates they have their own parking space) and is related to a Curie.

What one must consider is that out of the estimated 108 billion people that have ever lived, only 900 have won this prize. Clearly this is not the best indication of genius. There must have been a good number of other inventors and problem solvers that have lived throughout our time, and not all of them were 61 year old Harvard alumni. It is interesting that humans always look at the exceptional, when really everything we currently understand about human intelligence is based on the average. We tend to think genius is based on how much you’re above the average IQ. Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking had MENSA IQs of 160. But Richard Feynman, widely regarded as a genius, only had an IQ of 120. In addition, last year, a 12 year old girl got an IQ score of 162. Does this mean she will develop the next theory of relativity? Unlikely. Child protégés do not typically remain that way as IQs change over time. In a great article “What your IQ score doesn’t tell you”, the writer goes on to describe that the test doesn’t tell one about the ability to perform tasks or make things work – a pretty big part of life really. IQ is not the same as “common sense” and is certainly not the same as intelligence.

“Intelligence” as defined by Dr Robert Sternberg is made up of 3 facets: analytical skills, practical ability and creativity. You need some common sense to make that IQ work. But perhaps what truly distinguishes genius is not just a Nobel prize, crazy hair and marrying your cousin (something Einstein did) but how creative you can be with the world around you. Einstein and Max Planck were accomplished musicians (violin and piano respectively), Richard Feynman was an acclaimed artist and Marie Curie, well she liked to cycle. Creative people are generally polymaths, they have a wide variety of knowledge and skills and potentially we should focus more energies on other creative pursuits than just work. And while you certainly can’t learn to be a Caucasian bearded man, one can encourage creative behaviours. While some imagine that the coffee breaks during the Savoy conference were packed with Physics, its highly probable that Albert whipped out his violin and Max joined in on piano, while Erwin Schrodinger made a few bits of furniture for his latest dollhouse, Marie went for a brisk cycle and Niels Bohr played a bit of footie.

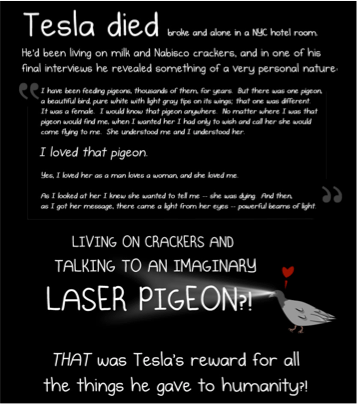

You will never influence the world trying to boost your exceptional IQ, or fitting into the “workaholic” mould. Be different; feed your creative side. Heck, keep pigeons if you have to; it worked for Tesla (well sort of)!

An excerpt from “The Oatmeal’s” cartoon“Why Nikola Tesla was the greatest geek that ever lived”, a truly great read!