So do you believe in life after death?

Awkward way to start a blog, right? I know! If you do, then I’m sure you’ll paint me a portrait of how it’s better than your current life. Where there will be no guns, no wars and hopefully no sugar tax. I guess if you want to get out of this life alive, there’s always a need to believe in something bigger and better than rising petrol prices and the depreciation of the Rand. So why do I ask? Well, because that’s exactly how I felt about my research. If you’ve read my last blog entry, you’ll know that my Master’s journey has been nothing short of novel drama. To keep myself sane during that period, I just imagined a time after data collection where I would just analyse my data, start writing up and submit after a week. For the most part, that dream kept me going — but imagination and reality are two different things.

When things don’t go your way through the practical phase of your MSc or PhD, you imagine your last day of data collection. You daydream about how nice it will be and how you’ll virtually have your qualification in your hand.

It’s only when you actually get all that data when reality really hits you like a one ton truck. When you fill in the last digit on your diary, you breathe a sigh of relief. Happy, and reminiscing about all the days when you thought your experimental diets would run out, or when load shedding nearly killed your day old chicks; surely nothing can be worse than that. It is only when you open your Excel sheet that you realise that a new chapter in your Masters tale is about to start: your “life after data collection” chapter. Having to punch in data acquired over a seven week period is no child’s play, especially if the data that you have is for more than 10 dependent variables.

My data capturing was kind of fun, I mean I had been looking for this data for 2 years and finally I had found it. I felt like I owed it to the Almighty to push on with a smile on my face. The crazy part is that as each digit left my diary and into the excel sheet, so did my smile. By the time I finished entering my data I was tired, exhausted and so drained.

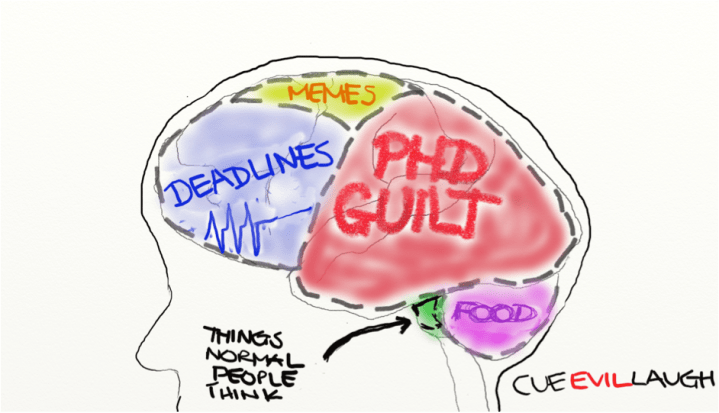

With all the data sorted, the next step was data analysis. I think this is the part most students dread. Having to sort your data is one thing, but knowing what it all mean is a challenge for most. At what level are you testing? What does the output mean? How do you express this data? I bet these questions make most postgrad students wish they had paid more attention to their Biometry lectures.

Fortunately, at University of Fort Hare, we are blessed with minds that eat data analysis for breakfast, lunch and supper. Who knew having to wake up early everyday to attend the experimental design and data analysis class would help? (Hahahaha I hope my supervisors won’t be reading this.) The thing about analysis programs, is that if you can’t speak their language then you are doomed, if you can’t tell it what you want It to do then you’re better off sleeping in your room. For me, the program was fine … the problem was with the user (me). I had an idea of what I wanted to do and how I wanted to express the data but the way I’d analysed my data didn’t allow me to. I was busy running up walls and pulling out my non-existent hair!

That was till I decide to speak to my varsity friends and mentor, Thuthuzelwa Stempa, Xola Nduku, Soji Zimkitha and Lizwel Mapfumo. Having to brainstorm my intended outcomes and data expression made an HUGE difference.

So here I am, sitting at the lab and finishing up my graphs and writing up, imagining myself walking up to collect my second degree and making my family proud. I hope that this time my imagination won’t be too far off.

So what did I learn? Life’s filled with challenges, and the very same sentiments echo through your research life. Be it admin, data collection, data analysis or writing up. Your life after data collection might be better than mine or worse, but the moral of the blog as always is about grinding it out, spin those numbers to letters and making sure you graduate in time.