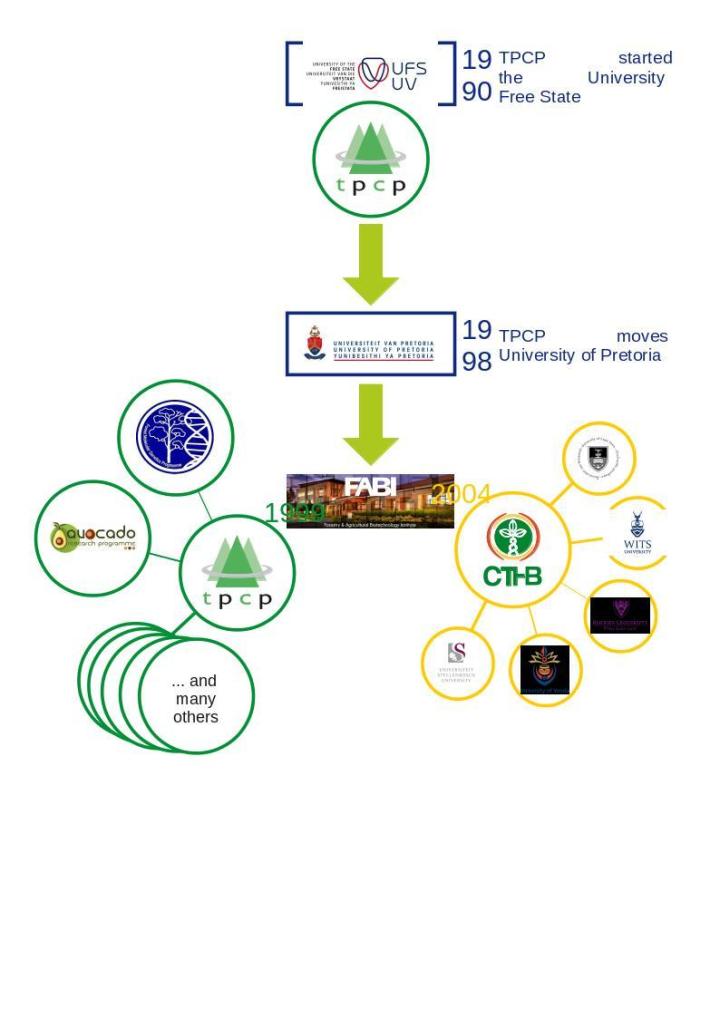

In 2004, the Department of Science and Technology (DST) with the National Research Foundation (NRF) established the first seven Centres of Excellence (CoE). These Centres, based on the successful CoE models implemented overseas, were adopted to build on existing capacity and resources but also aimed to bring researchers together to collaborate across disciplines and institutions to drive science excellence.

I joined the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI)–the host institution of the Centre of Excellence in Tree Health Biotechnology (CTHB)–in 2008 when I started my Honours degree. At the beginning on my Honours, I didn’t quite understand what the Centre of Excellence was or why it even existed. How “excellent” was this programme? Was there a need for tree health research in South Africa? I was really only concerned about doing well and learning as much as I could so that I would be a better candidate for a Master’s. But my eyes have opened up since then.

Between my classes and research project, I was encouraged to get more involved in the CoE’s activities by volunteering to be a mentor for the undergraduate mentorship programme, working in the Diagnostic Clinic (which services both the CTHB and TPCP), attending workshops run by Dr Marin Coetzee, who conducts some of his research in the CoE, and so on. The CTHB–true to the purpose of the Centres–made more room for excellence; more postgraduates could complete their studies through FABI, more essential equipment could be bought, research could include other sectors and not threaten industry-specific funding, opportunities through workshops and collaboration started to grow, leveraging funding and excellence became more important, etc. The CTHB – a virtual centre run through FABI – became a critical part of FABI and because of that, the CTHB absorbed some of its excellence, built on it and delivered its own excellence.

I experienced how research can truly grow and have international reach. As the CoE’s research net widened, we started to identify more and more problems of concern to plant health in South Africa—many of them brought on by climate change and globalization. Because of the limited capacity in the country, back in 2004 to deal with pest and diseases that were arriving from other parts of the world, the importance of national and international collaborations and knowledge exchange became a priority. These close connections–that are still being built and expanded today–have led to growth in South Africa’s capacity; not just around FABI but at all the institutions linked to the CTHB. In 14 years, the CoE has produced 786 publications, 125 students, and really changed the ways in which we understand diseases of our native plants.

As a student associated with a CoE, I have had better opportunities for funding, wonderful teaching, mentorship, collaboration, and international exposure. Like those that have come before me, I plan to contribute to the science excellence in the country and grow more excellent people. No matter what happens to these Centres in future, as funding continues to dry up, we need to remember to keep excellence at the centre of anything we do—for us, for our country and for the world.

The solutions to South Africa’s and the world’s problems, according to Obama, lie with the youth; an undivided youth who love more, who lead and build communities that fight for what Mandela, and others, were and are trying to build. I was inspired by Obama’s messages of hope and the vision he has for achieving an undivided, educated and loving global community. I want, more than anything, to be a part of that community.

The solutions to South Africa’s and the world’s problems, according to Obama, lie with the youth; an undivided youth who love more, who lead and build communities that fight for what Mandela, and others, were and are trying to build. I was inspired by Obama’s messages of hope and the vision he has for achieving an undivided, educated and loving global community. I want, more than anything, to be a part of that community.