Throughout my academic career I have been told that once I complete my studies the doors of opportunity would fly open for me. I have not found that to be true. Getting a secure job, or even accessing the funds to create your own job, is not guaranteed. A study undertaken by Dr Amaleya Goneos-Malka found that a PhD may actually decrease your employability as this qualification is not necessarily valued outside of academia. More than once, I have had to climb laboriously through narrow windows because those proverbial doors never just sprung open. With this experience it is strange that I haven’t been more intentional or strategic about preparing for the world of work and life post-PhD.

I recently started a process of finding out which skills I have that can be transferred to industry outside of academia – just in case my original plan does not pan out.

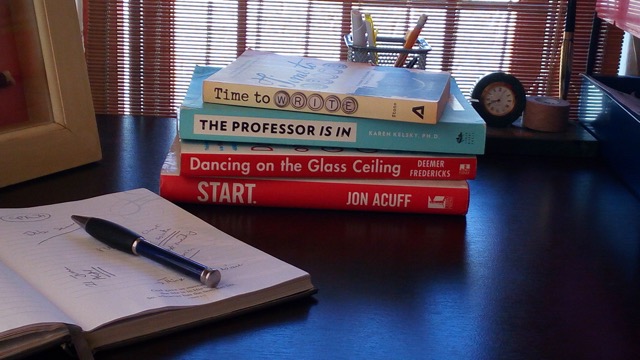

Getting an academic job is no mean feat. A short while ago I read a book called the ‘Professor is in’ by Professor Karen Kelsky. Actually, I received the book as a present a long while ago, but I was too afraid to read it. In a nutshell, Kelsky lays out the skills and techniques that doctoral candidates need in order to secure a tenured position at a university. And yes, the South African market is not the American market, but we’re heading straight there. I found Kelsky’s book simultaneously comforting and frightening. Comforting, as she lays out a roadmap to follow in making yourself marketable for an academic job; frightening, because she also paints a very bleak picture for those who wish to follow the tenure track. The crux of what I got out of the book is that: to be competitive, you need to be intentional about the additional skills you acquire over the course of your degree, and you also need to package yourself appropriately; YOU are the product.

Getting an academic job is no mean feat. A short while ago I read a book called the ‘Professor is in’ by Professor Karen Kelsky. Actually, I received the book as a present a long while ago, but I was too afraid to read it. In a nutshell, Kelsky lays out the skills and techniques that doctoral candidates need in order to secure a tenured position at a university. And yes, the South African market is not the American market, but we’re heading straight there. I found Kelsky’s book simultaneously comforting and frightening. Comforting, as she lays out a roadmap to follow in making yourself marketable for an academic job; frightening, because she also paints a very bleak picture for those who wish to follow the tenure track. The crux of what I got out of the book is that: to be competitive, you need to be intentional about the additional skills you acquire over the course of your degree, and you also need to package yourself appropriately; YOU are the product.

If I had the opportunity to go back in time, I would have done things a bit differently from the start of my PhD, which includes being mindful about opportunities in the private sector. Below is a list of four things that I would have done differently (and I am working on correcting):

- Develop three different aspirational resumes: one for the corporate world, one for the NGO sector and, one for academia. These resumes would be modelled on the skills and expertise that I need for each sector. The idea is that by the time that I am done with building up my skills, I have three different areas that I have the capacity to enter based on my initial skillset and area of interest.

- Learn how to network better. I do not understand how networking really works although I know it is important. I am never sure what I am supposed to say to strangers and how to cultivate professional relationships outside of my area of expertise. I have made it my mission for the rest of the year to get better at building relationships.

- Be more adaptable and always have a willingness to learn. The reality is – the world has problems that need to be fixed. I need to adapt my skillset to meet the ever-changing challenges ahead and never say NO to learning something new. I am kicking myself for somehow Unlearning how to be adaptable:While studying towards my undergraduate degree, I worked part-time as an outbound insurance telemarketer. I was forced to learn about various insurance products, but I also had to learn how to “sell”. I earned a pretty decent commission on top of my basic salary. What I learned in that call centre is that your primary job is to figure out what your customer needs and give it them. Somewhere along the line I lost that person, who was always ready to think out of the box to meet society’s needs.

- Make better use of free university workshops while I can. I have come to realise that many of the capacity building workshops that are offered for free at university, such as journal writing or learning how to use the latest software, are worth a premium outside the ivory towers. All that it costs me is time and a few weeks of commitment but the rewards are immeasurable.

My list is not in anyway complete, as I am working out the details. I plan to book a few sessions with a career coach in the near future to help figure out how to navigate my post-doctoral life. I would appreciate any tips that you may have in the comments section below.