Bridging the gap between academia and the real world is so important. For starters, if our work is not impacting the communities we write about or the world we live in, then what is the point? In my discipline of political science (and especially in gender politics), there is a lot of confusion about the terms that are used. If political science is the study of the world we live in, and gender studies is the study of gendered dynamics in the world we live in, gender politics brings together the opportunity to study what happens in the world with a consideration of gendered power dynamics. There may be some terms that you recognise, as they have made their way into mainstream language. As a result, it becomes difficult to separate fact from fiction when originally academic terms become part of the everyday lexicon. This blog will be decoding eight terms within gender politics (with some others sprinkled in between!). The hope is that this can help foster a deeper comprehension of critical issues at the heart of these areas.

1. Gender: Gender is the expression, behaviour and identity through which you experience the world. The genders that society is often familiar with are ‘man’ or ‘woman’, but there are a plethora of genders that people identify with (or don’t identify with e.g. non-binary people/gender non-conforming people). It is essential to know that people’s gender expression (through clothes, hair, behaviour, voice) is not the same as gender identity (which has to do with self-identification), or sexual orientation. Within feminist scholarship, there are also those that challenge the idea of gender being a separate categorisation, they state that a binary understanding of the body is a product of social-cultural realities.

2. Feminism (feminist theory): Depending on where you get your information from, the term feminism can be defined on a wide spectrum. But is there a ‘right’ definition of feminism, and what would an accurate example of feminism be? This is a difficult question to answer in a straightforward manner. According to UN Women, feminism is “a movement advocating for women’s social, political, legal and economic rights equal to those of men.” Feminist theory is different in that it is a way of thinking and understanding how gender affects people’s lives. Examples of prominent feminist theorists include Sara Ahmed, Judith Butler, bell hooks and Ama Ata Aidoo.

3. Neo/liberalism: Within the discipline of political science, liberalism refers to a specific school of thought. Liberalism refers to the ideology of individual autonomy against state intervention. Over time the term evolved to also include protection against private businesses. However, in mainstream media, liberalism often refers to being a ‘liberal’, which is different from leftist ideals. Neoliberalism refers to the economic policies that highlight the political ideology of liberalism i.e. minimal state intervention, a competitive trade market and the principle of self-efficacy.

4. Patriarchy/Toxic Masculinity: Patriarchy can be defined as a system or hierarchy in which gender inequality is perpetuated through the unequal distribution of power that favours men and oppresses women. Toxic masculinity is a result of patriarchy, whereby the attitudes and behaviours of men towards women create a sense of entitlement towards violence and dominance. A popular example of toxic masculinity is the TikTok famous social media personality Andrew Tate, whose views and beliefs on men’s and women’s places in society have had a massively negative impact on young men.

5. Intersectionality: The term ‘intersectionality’ was created by Kimberlé Crenshaw in the 1980s, which was meant to highlight the intersecting ways in which differences (race, class, gender) amongst groups of people showcase imbalances in the legal context of the USA. However, intersectionality went mainstream around the mid-2010s, and the conservative backlash to the term created a fear-based idea about who deserves to be a victim, and who does not. At its core, intersectionality functions as an observation of power imbalances in varying socio-political contexts and is a tool through which said contexts can be examined and dismantled.

6. Cis-hetero patriarchy: There are three different terms in this one word, namely; cis-gendered, heteronormative and patriarchy. We know that patriarchy is a system that prioritises men by valuing behaviours, attitudes and systems that oppress women. Heteronormativity is the assumption everyone is ‘naturally’ heterosexual (romantic/sexual attraction to people of the opposite sex i.e. heterosexual men are attracted to women, and vice versa). Cisgender is the gender identity of a person who identifies with the gender they were assigned at birth. Therefore, when we put it all together, cis-hetero patriarchy is a “system of power based on the supremacy of cis-gendered heterosexual men through domination and exploitation of women and other marginalised genders/gender nonconforming identities.

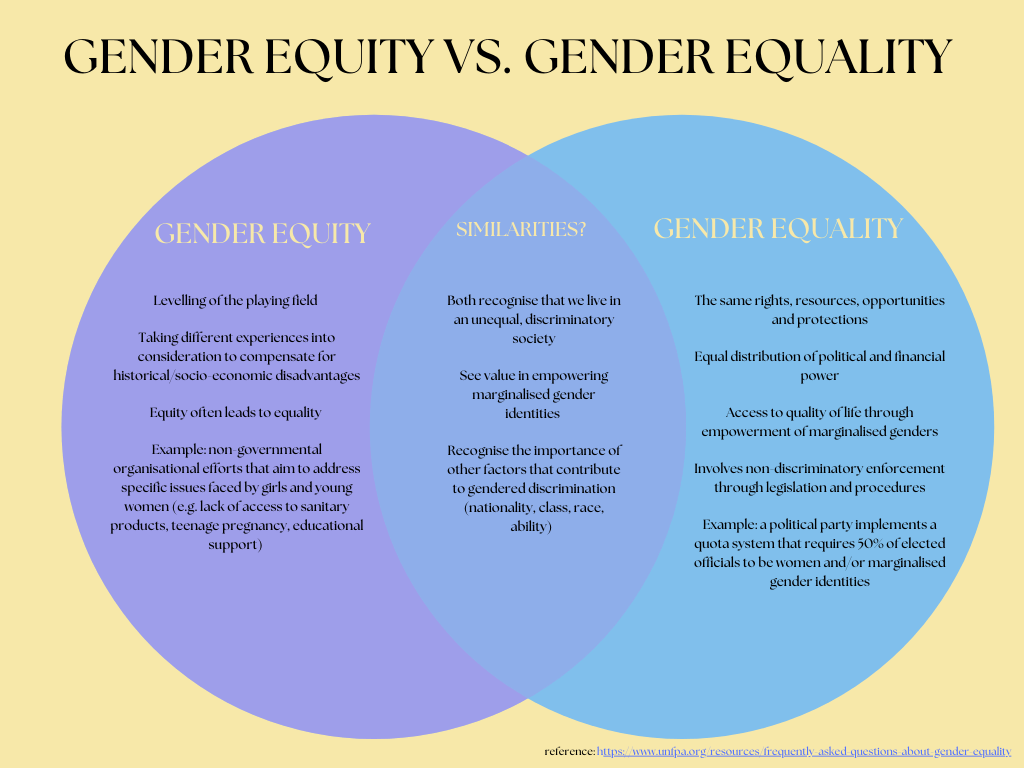

7. Gender Equity/Gender Equality:

8. LGBTQIAP++ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer, Intersex, Asexual, Pansexual, and more): This is an acronym that has changed over time to reflect other identities not included. Although it is shortened to LGBT, this can have different implications for those who do not identify as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual or Trans. The earliest use of the term LGB was in the 1990s when lesbian, gay and bisexual activists adopted the acronym for the community they were part of.

Maybe other terms came to mind when reading through this that you’d like to understand more about. Also being aware, there are different implications for these definitions when applying them to different contexts and examples. Let me know in the comments below!