A year and a half into this PhD journey, I am at that stage where I can see where I fulfilled the goals I set, and the ones that have to be adjusted. Between me, myself and I, everything feels a bit messy lump of tangled deadlines that seem to grow longer with each passing day. But, against the backdrop of having presented at local and international conferences this month, making worthwhile connections within my field, and meeting some amazing radical feminists, I can’t help but feel a divide between what I see and what I feel. That divide is further complicated when I consider the difference between how many of us may feel internally about our progress, and how others see our achievements. But I think for many overachievers (and people who tend to be hard on themselves), by the time you accept the one accolade, your mind has already moved on to the next thing to accomplish.

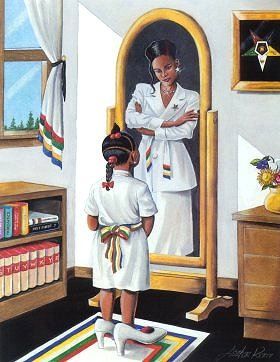

So for this blog, I thought I could reflect on what it means to feel dissonance between who we are and how others see us. I am not the first person to have this thought, but I think it’d be worth it to look at it from my perspective. What does it mean when we are functioning at our highest self? Why do we worry about who we are around others? Especially when we’re not all meant to be in the same space? I often have to remind myself that even if it’s not exactly how I thought it would turn out at the time, that 15-year-old Ijeoma would be so amazed at this current version of Ijeoma (and slightly in awe). Someone once said that we often work to make our inner child happy, and I can’t help but feel like this is the most important thing to me regardless of what I do. My funny, thoughtful, caring side deserves tending to, which means letting go of trying to extend that to everyone you come across. Making others comfortable in a space is a very valuable skill, but it took some time to realise that one does not have to centre your life around being universally palatable.

It’s also not lost on me that August is Women’s Month in South Africa. When I reflect on what empowerment means to me today, it no longer holds weight when I think about my womanhood. Especially when we see how empowerment serves as lip service to ensure inequality remains the status quo, and the word itself functions as palatable activism to achieve superficial institutional and organisational objectives and goals. Defining who I am as a woman becomes about the integrity and principle behind each action and decision that is made towards my own and others’ emancipation. And that’s where I find myself most times – attempting to fuse these floating parts that feel like they operate in isolation from each other. But the funny thing is that in most cases, everything is connected. In Japan, their philosophy of Ikigai centres around your reason for being; the thing that drives who you are, your essence and purpose. If we know that we all have individual gifts, then it makes sense that it is up to us to indulge in the life-long journey of slowly unwrapping it – and then presenting it to the world.

So it’s okay for others not to get it. To not get you. Being an outlier shows that you contribute to society’s betterment before you may even know what your potential impact will be for years to come (it happens to many). But, staying aware of what keeps you grounded makes the reflection clearer. Nurturing and fostering a strong sense of self can help us stay on track to being part of something bigger than the perceptions of others. A sprinkle of daily gratitude doesn’t hurt either – as long as we know the only person we are ever in competition with is ourselves.