Zamancwane Pretty Mahlanza

When travelling, incorporating Indigenous edible foods into our diets provides a wonderful way to connect with the land and the cultural legacy of different native populations. Indigenous foods are frequently grown responsibly and are very nutrient-dense. Some of these items include underutilised and neglected food groups, such as cereal grains and wild edible plants. Understanding these crops origins, techniques of harvesting, methods of preparation and processing, and their nutritional benefits for people is necessary to get these foods from the land to our plates.

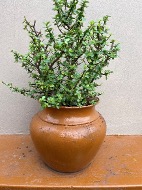

The consumption and usage of Indigenous food sources offers nutritional and health-promoting benefits. Cereal grains such as the finger millet are rich in calcium, dietary fiber and are gluten-free grains (figure 2). In addition, the spekboomplant leaf (figure 1) are, also referred to as the carbon capture powerhouse is an edible and medicinal plant leaf rich in vitamin C and antioxidants. Furthermore, these crops and edible plants aid in diversifying the food supply and enhance global food security. By expanding the range of crops and foods we rely on, we reduce the risk of food shortages due to pests, diseases, or changing climate conditions.

Figure 1: Spekboom plant leaves

Figure 2: Finger millet grains

Our global food systems are interconnected, and I believe that this phase of my academic research where I develop instant food products and 3D printed snacks (figure 3) by using traditional and novel food processing techniques in underutilised and Indigenous food sources to improve nutritional value, functionality and health promoting benefits. Sustainable foods and technology are some of the key themes that my research topic focuses. Additionally, these are the two factors that will directly reshape consumer’s food perception in the immediate and near-term future.

Figure 3: 3D printed biscuit

Growing up I watched my father working hard in planting and harvesting crops in our community garden. At the time, I didn’t realise I was witnessing an unspoken knowledge system, one that held nutritional, ecological, and cultural value. It wasn’t until I began my studies in food and consumer science that I recognised how indigenous foods, long overlooked, could help reshape our global approach to food security and sustainable diets. Despite increasing interest, the rediscovery of indigenous foods remains fragmented. Much of the scientific literature is limited to isolated case studies, and not entirely on the of efficiency of safe processing that can increase the nutritional value and health promoting benefits. What’s needed is an interdisciplinary approach, one that combines food process engineering, food chemistry, and new product development.

At the Centre for Innovative Food Research, were my current PhD research is based on food processing engineering, food chemistry, new product development and sensory analysis. The hands on experience here has been invaluable, shaping me into a researcher who thinks outside the box, pushes boundaries, and develops real-world solutions. I’ve made progress in focusing in identifying the metabolite profiles of processed finger millet and edible cricket whereby the study’s findings provide a crucial framework for tracking and controlling the metabolite composition of FM and EC flours during traditional and novel processing https. In addition, highlighting the application of efficient processing (traditional and novel) techniques have made improvements that suggest that combining the processed flours could yield a composite product rich in protein, with improved nutritional content, functional properties, and potential health-promoting benefits https://doi.org/10.1093/ijfood/vvaf056. As we journey back to our roots through the rediscovery of Indigenous foods, we uncover more than just forgotten flavours and implement new food processing techniques, we also reclaim stories, wisdom, and a deep respect for nature’s rhythm. The future of food may just lie in the past rich, resilient, and rooted in tradition.